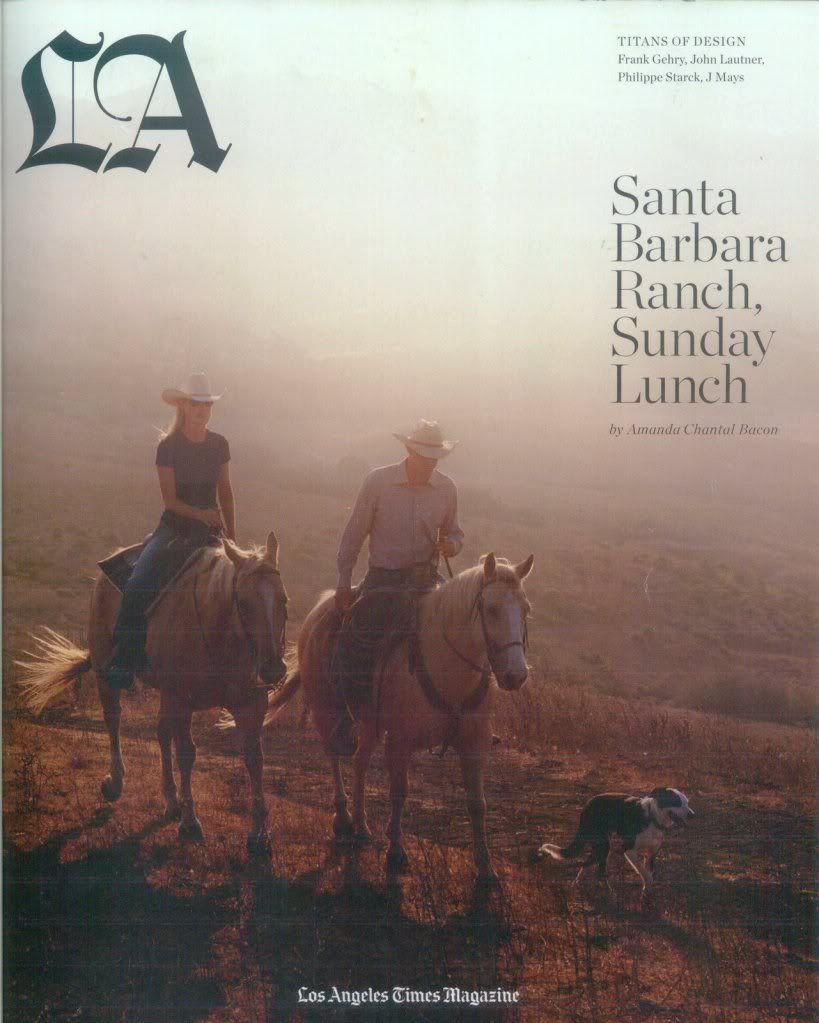

Up the coast, down the road and under the arbor at Rancho San Julian near Buellton, yellow jackets swoop through our lunch, falling into our wine, leaving behind smudges of pollen from the fertile Santa Barbara mesa. Jim Poett is pulling a bee out of his daughter's bowl of ice cream. His strong silence at the long table belies his pride in his daughter, Elizabeth Poett, 28. Jim is one of the first organic beef farmers, former president of the South Coast branch of CCOF ( California Certified Organic Farmers) and collaborator on the California Organic Foods Act of 1990. Just as Jim did almost 30 years ago, Elizabeth has returned home to her family's ranch from the big city. She has all the best intentions and is mentored by her father in order to realize her heroic visions of better beef. For Elizabeth, it's all about continuation and preservation of tradition, family, land, community—and feeding us really, really well.

The legacy of the Poetts' Rancho San Julian reaches back in history to long before California was a state—to when Mexico wrested Alta California from the Spanish. The land's original owner, Captain José de la Guerra y Noriega, Elizabeth Poett's great-great-great-grand-

father, had been

comandante of the Royal Presidio. Because of his aid in the junta against Spain, Mexico awarded him more than 100,000 acres of land throughout what were called at the time the Santa Barbara and San Buenaventura regions. After Alta California became a U.S. possession, his land remained. Indeed, de la Guerra y Noriega's family embraced the newcomers, literally. Three of his daughters—Teresa, Angustias and Anita—married Americans. And Rancho San Julian's 15,000 acres—14,000 of which are grazable—are still intact, one of the oldest family-run ranches in California.

Now Elizabeth focuses on steer-rotation cycles, worries about the effects of grass-fed versus grain-fed cattle, takes care of getting the steer bathed and wonders why one of them is making a snoring sound while breathing. The family's ranch is completely organic and sustainable and goes so far beyond free range and humane they stop just short of naming each one. I would venture to say the Poett cows are as happy as bovines can be. And for all we know, that's why they taste so good.

On this particular afternoon, a group of neighbors and friends, many of whom contributed the fruits of their labors, linger over the cleared lunch plates in the shade of Zinfandel grapevines, draining the last of the Pinot noir brought to the table by Tekla Sanford, who runs the nearby boutique organic winery Alma Rosa. They savor delicious perfumed heirloom melons from Chris Cadwell (of Tutti Frutti Farms) and José Baer's (of La Nogalera)

nusstorte, his old Swiss recipe made from Central-Coast honey and his own Chandler walnuts (grown in one of California's last walnut orchards). Lunch-table conversation for Elizabeth includes her plan for monthly 15-pound deliveries of locally produced meat to Southern California families, getting L.A. chefs interested in serving Rancho San Julian beef and opening the ranch to all visitors.

After lunch, as we stand in her office (very bohemian, modish, with doors that open onto one end of the corral), Elizabeth and I look at an-antique meat chart from Chicago that she found amid the ranch memorabilia. It shows the old-school breakdown of the cow. She feels it may be the right time to bring back some of the classic cuts of meat, like beef bacon, because cooks are moving beyond the safety zone of chicken breasts and filet mignon.

On the walls are a mix of family ranch photos dating back more than a hundred years, shots of her knee-deep in the ranch's lavender field, a dry-erase board listing the exact weight of all her steer and a pile of red lollipops for her youngest cousin, Isabella, and the children on the ranch who come to visit.

Beyond the office, Elizabeth's boyfriend, Austin Campbell, leans on the corral railing in boots and a hat, waiting for us. He is a bona fide cowboy and doesn't give a second's thought as he spits out the yellow jacket that landed on his lollipop. He's a rancher for a local government-run ranch and dairy. They fell in love after meeting two years ago at a branding at the ranch. She was covered in dirt and manure and had just performed a castration, and I imagine he was dumbfounded by her long blond hair and statuesque beauty. They now live surrounded by artichoke fields.

Elizabeth's mind is still on lunch. She is anxious to know how we feel about the fat content in the tri-tip her dad grilled. One bite, and we can taste that the soil has been nurtured to grow the cattle's feed and that the little bit of fat provides a distinct elegance and gratifying mouth-feel that renders easily on the tongue. She is conflicted: Whole Foods has told her that to be part of their program the ranch should have a sprinkler system (despite the water crisis) so there's always green grass for the cattle to graze on, because the term

grass-fed beef is good for marketing. Elizabeth isn't convinced. She thinks her cattle should eat a varied diet that includes organic hay and alfalfa as well as grass. She thinks it's better for the cattle and the sustainability of her ranch and asks, rhetorically, "What do chefs in L.A. want?" She already knows the answer: a product with the best flavor, and her grass- and grain-fed Angus delivers just that. Elizabeth's goal is to give a life to her cattle where "they get to live the way animals should live, and families can enjoy food in good health."

Our after-lunch tour continues. The Poett ranch house, built in 1817, is something of a Ralph Lauren set, Bob Dylan song and Lorca novel spoken by Steinbeck and frequented by Hemingway all rolled together. As we meander through the home's three wings, I have to keep reminding myself that what seems like a wrinkle in time is real. "It's like a museum, but you can sit on all the chairs. No one actually lives here full time, but the whole family shares it--we do brandings, lunches and reunions here."

In the cowboy dining hall, Elizabeth moves toward the head of the long, wooden dining table. Jim stands in the doorway, beaming as his daughter passes on her family's oral history: "A Chinese cook who didn't speak English and grew opium outside his bedroom window prepared three meals daily for the cowboys at 6 a.m., noon and 6 in the evening." Elizabeth veers from the tale to tell me about the year she spent in Seville and how she almost didn't return. She reminisces about her job in TV production and the great hole-in-the-wall apartment on Thompson Street in Greenwich Village. Seeing her standing at the head of the cowboy table, you can't imagine her living anywhere but this land.

We take our black coffee on the front porch under the trellised Cecil Brunner roses. I'm sent off with an armload of zinnias. Then, with reluctance, I travel back to the present, up that road, down the coast and back on Mulholland before sunset.